Paved by the will of the people – in 2016

Originally published here and here

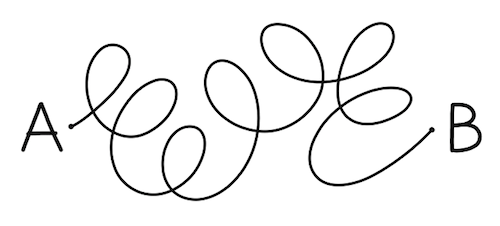

Throughout the labyrinthine meanderings of Britain’s decision to leave the European Union, there has been, to my mind, a single recurring thread. It began almost immediately after the vote – a week or two on, once the initial shock had dissipated and the reality had set in. People from across the political and societal spectrum began to embark upon what would arguably become the greatest exercise in speculation, followed by condescension, of modern times. They attempted to guess what the entire British electorate was thinking on June 23rd 2016 – and then they told them what it was.

It was reasonable enough to wonder, given that this referendum result shocked at least half the country, most of Europe, and large parts of the rest of the world. Such an unexpected outcome – for so it was – certainly merited thoughtful analysis and perhaps even tentative conclusions over time. One might have expected a sober reflection on the causes and consequences of this vote to follow – but it did not.

Almost as quickly as many public figures had started to ponder, it seemed, they had stopped. Conclusions were drawn almost instantly, on both sides of the debate. From the Remain camp came the notion of ‘a howl of rage from Middle England’; from Leave came a triumphant self-affirmation that ‘the people were taking back control’. Both evolved into innumerable permutations of the arguments that both campaigns had made, and both went on to lead a life of their own.

Politicians, pundits and academics of all colours took to the airwaves to explain to us both what we did or did not vote for, and why. “Nobody voted to be poorer,” one of them would cry. Up would pop another saying, “the people voted to end free movement”. “Leaving the Single Market wasn’t on the ballot paper,” came many a riposte, only to be countered by an impassioned plea to “deliver the Brexit that people voted for”. In truth, neither side was any less guilty of this than the other. None among the chattering classes could be certain of what the result was founded upon, but instead of acknowledging their own guesswork for what it was, far too many soon came to view their own interpretation as akin to Gospel truth.

To an extent, at first, this did not matter. We, the people, had put our faith in the Government to go to Brussels and negotiate firstly an agreement to facilitate our withdrawal from the European Union, and secondly a comprehensive accord that would define our relationship with Europe for many decades to come. However, it has now returned from the negotiating table with the first of those, and found that it is highly unlikely to pass the House of Commons. The EU, for its part, has been very clear that it will budge no further. Parliament is now in crisis, with no clear majority seeming likely for any course of action to take us forward.

And so, today, we stand upon the brink. Many voices demand a re-run of the referendum to break the impasse, asking the country to vote again, while others say this would be disastrously divisive for the nation and serve merely to pursue the agenda of those whose worldview was shattered on the morning after the referendum. It would also take far too long to organise and implement, and it would be expensive in more ways than one.

But there is a way to ask the people to explain what they wanted, without asking them to vote on the matter again. This is a serious proposal for a 21st-Century country facing political deadlock.

When my County Council decides to review who remains eligible for a Single Person Discount on their council tax, they send me a letter containing my council tax account number along with an access code, asking me to visit a web address to complete their survey. This approach provides security and ensures that my responses are genuine. I see no reason why, in today’s world, we could not do something similar to poll the public on Brexit, using methods and tools that we already have at our disposal.

This would not be a further plebiscite in the sense of the 2016 referendum. We would not be demanding that the people vote again, as the EU has done to its member states so many times, nor would we be posing a different question or calling for a different conclusion. Rather, we would be asking the public to explain why they voted in the way they did, instead of telling them as so many figures have tried over the past couple of years.

We could use National Insurance numbers along with the access code approach for verification, although these would not be stored alongside the results, serving merely to provide for legitimacy and to ensure that no-one could use the online portal more than once. Having first indicated which way they voted, the portal would then ask citizens to explain their decision by ranking or selecting from a range of different priorities. For those without easy access to the web, a returnable form could be included with the letter, to accommodate responses by post. Essentially, this would be similar to the survey carried out by Lord Ashcroft on the day of the referendum, but opened up to the entire electorate instead of the (albeit impressive!) sample size of 12,369 that he obtained. For Leave voters, it would be indicative of the change they wished to see. For those who voted Remain, it would reveal the country’s concerns about that change.

Having analysed the results, the Government could then choose a path that most closely matched the priorities of the electorate. If ending free movement and regaining full parliamentary sovereignty over the law of the land were to emerge as the strongest themes, for example, then to leave the EU without a deal would seem to best respect the will of the people. However, if those factors were deemed less important than seamless free trade with Europe but with the ability to explore trade arrangements with the wider world, while saving at least some money, then perhaps a Norway/EFTA model would be more appropriate.

However it turned out, the Government could then bring a new plan before the House that bore the distinction of a legitimate democratic mandate – just as it did before when an overwhelming majority of MPs voted to trigger Article 50, despite their own personal feelings. To implement what I am calling for would be significantly quicker, easier, cheaper and far less controversial than calling for a second referendum, and would finally restore direction to the Brexit process. With the passing of Dominic Grieve’s amendment on January 9th, the Government is obliged to make a statement to the House presenting its next steps within three days, given that the Withdrawal Agreement has been voted down with such a crushing majority. If the calls for a second referendum now intensify, perhaps this could be it.