Politics are going on as much as economics here

Originally published here

One thing is clear from the decisions announced in yesterday’s Budget statement: politics are going on as much as economics here.

For the past few months, the mantra of many vocal voices on the left has been: “don’t let them make the workers pay for this crisis”. By raising Corporation Tax in this way – albeit with a delay – the Chancellor is seeking to deflate that argument.

The taper scheme means that those who trade as a business rather than as a sole trader, but whose earnings do not exceed what one might expect from a typical ‘established middle-class’ salary, will be totally unaffected by the tax rise. Only the top 10% of businesses, with annual profits in excess of £250,000 per year, will bear the full brunt of the new 25% rate.

The two-year delay gives bigger businesses time to leave if they want to – and some might. However, various other pro-business incentives in this Budget that have been welcomed by those on the right – such as the announcement of 8 free ports and the 130% tax offset for investments – ought to encourage them to stay instead.

This is nonetheless a big gamble, on both a national and an international scale.

At the same time, the Chancellor is saying that income tax and National Insurance for individuals will not rise, and that the personal tax allowance will not fall – although, after a very small increase next year, nor will the latter rise for the next 5 years after that. Duties such as those on fuel and alcohol, which generally tend to rise every year, will also not be going up.

Then again, that should not come as a particular surprise to anyone who read the Conservative Manifesto in 2019 – it promised not to raise income tax, National Insurance or VAT in the lifetime of this Parliament.

All in all, this basically means that it will in fact be the highest-earning businesses with large profits that will be asked to pay more towards rebuilding the country’s economy in the wake of the Covid pandemic.

Individual workers, including the very poorest, are not in principle expected to lose out much from this Budget. This, at least, is the perception the Government will be hoping for.

As ever, though, it is more complicated than that. For example, ten years or so ago when the Coalition Government was raising the public sector pay spine by only 1% per year (and calling that a pay rise), the trade unions pointed out that, with inflation running at 3%, this actually amounted to a real-terms pay cut of 2%, year on year.

That same argument will probably be made again now, in respect of the personal tax allowance not rising in line with inflation.

However, this does hint at a note of optimism from the Chancellor, in that he seems to be anticipating that inflation and interest rates are not likely to skyrocket out of control over the next 5 years.

Indeed, his reliance upon the OBR’s forecast that the economic position will be getting back to normal by the middle of next year (which some have said looks too optimistic) also appears to stem from a similar instinct.

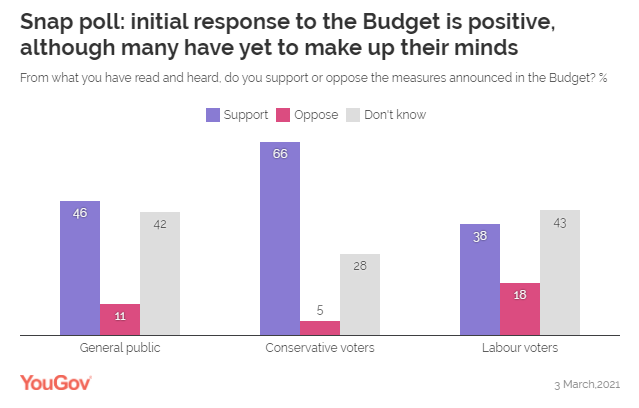

Initial public support for this year’s Budget appears to be positive, according to a snap YouGov poll conducted yesterday:

Only time will tell how well this initial support holds up in the coming months, as the country begins to emerge from the most devastating pandemic in a century.